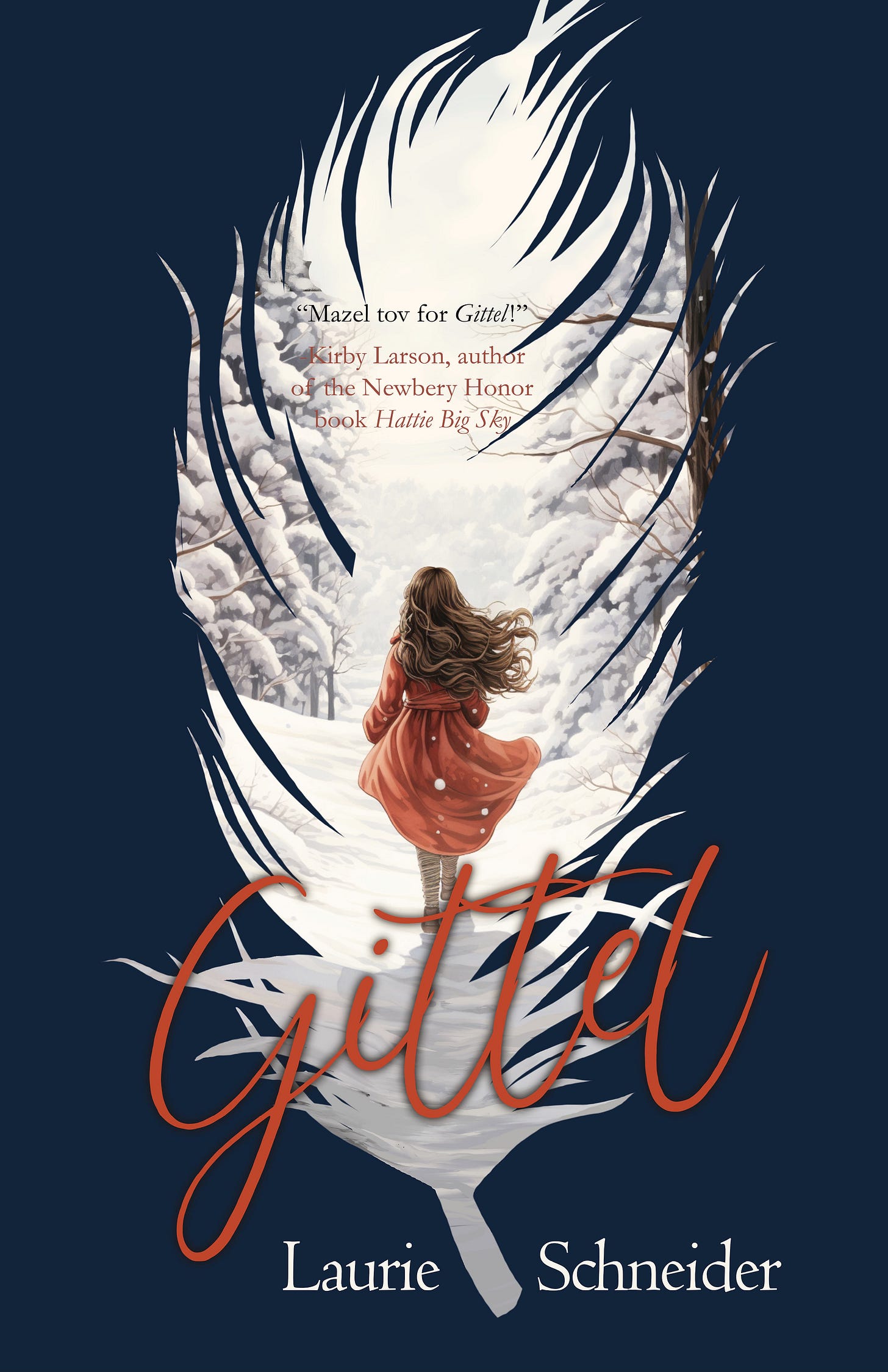

Today I’m chatting with author Laurie Schneider, whose debut middle grade novel, GITTEL, is out now. It’s the story of a turn of the 20th century Jewish girl whose immigrant family settles in rural Wisconsin to farm. If you’re looking for a good middle grade historical that I highly recommend this quick and engrossing read! The rural farm life setting sets this one apart from the typical New York Lower East side stories, and opens up a new world to readers young and old. And I’m so glad I had the chance to ask Laurie about all that and more. Our conversation follows. I hope you enjoy.

Joy: I know that a large part of your inspiration for GITTEL comes from your great grandparents, who were members of a small Jewish agricultural colony in Wisconsin in the early 1900s. Their story also inspired your master’s thesis. Can you talk a little about those real Jewish farming pioneers and their experience in the diaspora of the Midwest of the early 20th century?

Laurie Schneider: I’ve always been fascinated by utopian back-to-the-land movements. It never occurred to me that my own family had a connection to one of these movements until I began researching Jewish agricultural colonies. It turns out the history of the movement is fascinating and more than a little fraught.

A bit of backstory… As Eastern European Jews fled persecution and pogroms in the late 1880s and early 1900s, New York City was overwhelmed with immigrants, with families packed into cramped tenements with poor sanitation. The Jewish Agricultural Society funded and sponsored farm colonies in various parts of the country to alleviate the overcrowding and stem rising antisemitism. The colonies, they hoped, would provide a healthy living for these mostly Hasidic Jews and also speed their assimilation, make them more American. And what could possibly be more American than tilling the soil? It was an idealistic vision.

There were a few colonies that had modest success, like the Alliance Colony in New Jersey, but in settlements farther from New York, things weren’t so rosy: Kansas, Colorado, Louisiana, the Dakotas. Most colonies failed within two years. Harsh climate, poor soil, isolation, illness, drought, fire, floods, crop failures, and lack of experience all contributed to their demise. The Wisconsin colony, where my great grandfather lived, was a triumph in comparison and survived fifteen-plus years into the 1920s, although there were only a few families left in the end. Falling milk prices, the lack of marriage prospects, and isolation from the greater Jewish community put an end to the colony. How do you survive in a place where there are no others like you? It’s hard. I know. I grew up thirteen miles from where Gittel is set. On the other hand, the movement did scatter the Jewish population beyond the East Coast, and while some of those original colony members moved to nearby small towns, like my family did, others made their way back to larger cities where there was enough of a Jewish population to sustain a synagogue.

Joy: That is indeed so fascinating, and a chapter of American Jewish history that not everyone knows. I’ve actually become a bit obsessed lately with the stories of Jewish chicken ranchers, particularly those who settled in Petaluma, California. They had an interesting run of great success! But back to Gittel herself, she’s a wonderful and feisty character. Did the idea for the novel come to you first or did Gittel’s character lead the way into the story? How did she become the voice of your story?

Laurie: I love your description of Gittel—feisty and wonderful. The setting came first, but I knew from the start I wanted Gittel’s perspective. My mother was called Gittel until she came to the US from Romania at age two, and my mother was indeed feisty and wonderful, though she hadn’t been born yet when the novel is set. In an oral history she recorded, my mother mentioned always wanting to be a “true American girl,” and that surprised me. My mother was so confident and seemed so proud to be a first-generation Jewish American I never imagined her wanting to be someone other than who she was. It only took a few pages for me to find that girl, brash and brave, but insecure, someone who adored her parents and yet was embarrassed by their accents.

Joy: I like that combination of brave but insecure. I think it made her feel very real to me. And speaking of things that tested her bravery, during the course of the story, Gittel experiences antisemitism, both in her small community as well as in the memories of what her family experienced during a pogrom back in Russia. Can you tell us about writing those scenes as well as thinking and talking about them now in our post October 7th world?

Laurie: My family fled Ukraine because of pogroms and over the years I’d heard bits and pieces of what life was like in my great-grandmother’s shtetl. She was alone there with her two little boys for seven years while my great grandfather tried to raise the money to bring her to Wisconsin. It was so dangerous she sent their teenage daughter—my grandmother— to live with relatives in Romania, which is how my mother came to be born in Kishinev. At one point, during a pogrom, my great grandmother later told my mother she spent an entire night cowering in a ditch with a corpse.

When it came time to write about a pogrom, though, I chose the Easter pogrom in Kishinev. It was the first pogrom documented by western media and the newspaper coverage caused outrage around the world. For the first time, people were able to read eyewitness accounts and see photographs of the massacre. I wanted to adhere to the facts as much as possible but my version of the pogrom is toned down; I wanted middle-schoolers to be able to read it. As hard as it was to write (and read) that scene, I feel it has to be there, not only to establish the violence Gittel’s family escaped, but the trauma they carry with them – even Gittel who wasn’t in Kishinev when the pogrom occurred. She feels the weight of it, and I want the reader to feel it too.

The bullying that Gittel experiences in Mill Creek has its roots in my own experiences with bullying and antisemitism as a kid, and I still find it hard to read some of those scenes, especially the remarks about Zayde, even though I wrote them! As for how things have changed since I wrote Gittel, which when I was first drafting, felt more like a quaint immigrant tale—a story of the past. Today her story feels more urgent and relevant in a visceral way– and not just for Jews, but for all marginalized groups being targeted. I desperately hope readers come away from this story with renewed compassion. I promise readers there’s plenty of light in Gittel’s story, too!

Joy: Yes, you definitely give the reader a full range of experiences for Gittel in her small Wisconsin town. And as for the setting, I see that you grew up in Wisconsin, although now you live in Oklahoma. Any thoughts on growing up Jewish in small-town Wisconsin? Or the Midwest in general? What would Gittel think if she were transported to the Wisconsin of your growing up years from her own?

Laurie: There were a handful of Jews in the town of 18,000 where I grew up…and I was related to all of them! While both of my parents were Jewish, neither were religious. So the extent of our family observance was kasha, matzo ball soup, and stuffed cabbage and the occasional trip to Milwaukee to visit my grandma and load up on bagels, lox, and chopped liver from Benjie’s Deli. But—and this is a big but—everyone in town seemed to know we were Jewish. I was very shy, and I didn’t want to stand out in any way. Sometimes this led to uncomfortable situations, like being called on in sixth grade to explain a Jewish holiday that I knew next-to-nothing about. I didn’t feel Jewish, but I was Jewish in the eyes of others, and of course as I got older and learned more, I came to see how very Jewish my upbringing was– and not the matzo balls, but my parents’ sense of humor, their Yiddishisms, their connection to the trauma their parents endured, their own experiences of antisemitism, their values, their community engagement, their political activism, the endless loud discussions over the dinner table. There are times I’m sorry for what I missed. I had no Jewish friends growing up, never went to temple. But I’m grateful for all the things my parents did give me. Gittel’s story is my tribute to my family, and I suppose, also an exploration of how my family became so assimilated.

How would Gittel feel if she were magically transported to 1972, the year I started high school?

Well, one thing wouldn’t change: all her friends would still be non-Jews! I do think she would be a little sad to discover that much of the Jewish practice she grew up with in her family was gone. But the freedom she’d have! She could check out all the books she dreamed of reading from the public library. She wouldn’t have to twist Papa’s arm to go to high school or college. I’m sure she would be loaded with extracurriculars: theater, choir, debate, lit mag, school newspaper. She’d probably argue with her teachers over the Vietnam War the way I did. And she would wear pants! Another thing that wouldn’t change: there would still be bullies, and Gittel would stand up to them.

Joy: Thanks for that thoughtful answer! Fun to ponder all the things that change and those that remain the same. And interesting observation that identity can be placed upon us even as we develop it ourselves. Lots of food for thought there. But what I most want to know next is: What’s coming next for Laurie Schneider?

Laurie: First off, a road trip to Wisconsin to introduce people to Gittel. And then it’s time to open a long-neglected folder of story ideas to see what calls to me. Probably another Jewish story.

Joy: I will be excited to read! Thanks, Laurie, for this great conversation.

For more on Laurie Schneider, plus a great GITTEL promo video, head to:

https://www.laurieschneider.com